Although we had wanted to leave Cuba for a long time -and daily life under Communism was as terrible as the stories a Hungarian refugee priest had once told us in my convent school "Dominicas Americanas", when he visited us after the Hungarian revolt in 1956- we had lived on a sort of 'limbo' from the moment our so called "Family Unit" (my then divorced mother, my brother León and I) had applied for a Permit to Leave.

It had been very difficult to convince our devoutly revolutionary father to agree for his children to leave the country for good. And the day he signed the Parental Permission at the Attorney's office, he fainted and fell on the floor to everybody’s dismay and my embarassement! And for months thereafter, my mother had waited many hours, sitting in our apartment’s balcony, overlooking 23rd. St., for the arrival of the "telegram" from the Ministery of the Interior that one day would "OK" our departure.

What instead "arrived" were 4 members of our building's "spy committee" (called “Committee for the Defense of the Revolution” or CDR’s for short) with a document in hand, filled with "15 grave counter-revolutionary charges" that would make our departure "virtually impossible".

This sudden event was something we never imagined could happen, since we were a pretty apolitical and quiet family; and although it was known to the CDR that we were not "pro-Revolution", we were SO afraid of everything (specially the CDR members!) we never did anything to provoke these "charges". After my father screamed and yelled that "because of stupidities like these, people took the illegal way out and escaped in boats" (since he was a pro-revolution writer -and a man- the cowardly 'spies' did not dare to say anything to him) we found that some of the "15 serious charges" were:

1) That my mother always dressed in black “as a sign of protest against the Revolution" (The truth was that her mother and brother had died recently and she was still wearing the traditional black "mourning clothes".)

2) That we went to a nearby church every Sundays and "loudly sang decadent Catholic Hymns". (True)

3) That we had applauded at a nearby movie theatre when the Metro Goldwyn Meyer's Leo the Lion had appeared on the screen, "as a sign of our love for the USA and our admiration for Capitalism" (We were definitely "guilty" of this one, since applauding at "American symbols" was one of the few ways we could protest; and apparently one of the 'spies' saw me and my brother doing it!) and....

4) That I had given my record-player to our cook, who had taken it out of the house "disguised in what pretended to look like a pile of dirty laundry".. (Guilty again!...I had done this after our house was "officially inventoried" by the Government when we applied to leave, and we substituted by brand new Hi-Fi with an old one).

Desperate, and not knowing what to do, and after many days of trying to pull 'strings' -even enlisting the help of many important communist figures from the Old Guard to help us untangle and clear the "grave charges" against us- the answer was:

“NO WAY! YOU CANNOT LEAVE THE COUNTRY!”

Although these charges might seem funny and even surreal in a ‘normal society’, in a Communist country were part of its everyday comings and goings; and the “Committee of the Defense of the Revolution” was high and mighty to the point that even important ‘party’ members -like writer and family friend Luis Gómez Wanguemert- could not override their authority to rule our lives.

Finally luck struck in the oddest way, when my mother remembered a Communist neighbor -Mayor Carlín de Varona- who had lived until recently next door to us; and the fact that one night -when their baby boy Robertico had been very sick- she had handed them, from our balcony to theirs, some "Paregoric Elixir" to calm the baby's cramps. They had been our neighbors for months, before we had learned that De Varona -a pudgy man of about 35, who dressed in nondrescript clothes and never wore his uniform- was a 'mayor' in the Revolutionary Army and an important government official. So my mother immediately became a "detective", located the new address of the family --and one afternoon we paid them a visit --totally out of the blue!

Needless to say, they were more than surprised to see us there -we had never been more than very casual neighbors! But once again St. Anthony of Padua (her favorite saint) came to my mother's rescue, as it turned out that Mayor de Varona had just being named "Head of Immigration" --and he was "the" man who had to sign and approve our departure papers! After sincerely explaining to his wife our problems, Mrs. de Varona -who knew we were not ‘integrated’ to the Revolution- was sweet and very understanding and promised “everything would be resolved”. When we finally left, ‘mami’ and I were trembling, our legs shaking of both nerves and fear. My mother's incredible Cuban-Basque courage had paid up once more!

(Many years after we left Cuba, we found out that Mayor Carlín de Varona killed himself with his service revolver. Many of Castro’s former comrades in arms have used "suicide" as the honorable way out of their dissapointment with the Revolution.)

A few days after our visit to the Varona’s, about 7 members of our block’s "Committee for the Defense of the Revolution" showed up in our apartment with the "Departure Permit" in hand; and the lengthy task of "re-counting the inventory" of the house, which had been written up 2 years before. As they counted the forks and knives, one by one, the realization of our imminent departure dawned on me and my brother. It seemed impossible, but it was happening!

As they checked out on the long lists the furniture, lamps, paintings and pots and pans, they went on to count -again one by one, yes!- every piece of clothing we were leaving behind.

"These panties must be the old lady's" -they joked around as they poked through my mother's lingerie and started counting mine- "And these smaller brassières must be the young girl's".

This is 100% true, I swear --- a totally surreal scene! My friends Marta Larraz and Jorge Costosa -who were visiting us that afternoon- kept saying to me in a low voice "Maria Antonia, we would have never believed this could happen...Only seeing it we can believe it!...It's a scene out of a Fellini movie"

After hours of re-counting absolutely everything in the house -and settling the squabble that took place --when they insisted our dining room table had originally been made "of mahogany" and now was made "of bamboo and glass, which shows Mrs. Ichaso that you have substituted it in order to fool us" -- the Committee President told us to get everything ready because he was ready "to seal the apartment, since you are leaving Cuba tomorrow morning and cannot sleep here tonight".

Leaving Cuba tomorrow?...This sent us all in a tailspin!...We were not ready yet!...At least I was not!..Nobody had told us this would happen so soon, since usually the permit was issued, and the actual departure would take place 7 to 10 days later. But the very cocky neighborhood barber -and a scrawny looking black man called Armando Valdes (who had lived in New York for many years before returning to Cuba in 1962 and becoming the CDR President) were in charge of the Spy Committee, and they were adamant, giving just 15 minutes to "pack the permitted pieces" of clothing ---and leave our home forever!

Right away my mother pulled from a closet the stuff we had been "saving" for the trip --and soon we were ready to go. It was so weird to just take off --and in a matter of minutes leave your whole life behind! There were still dirty clothes in the hamper, there was food in the refrigerator, beds were not even made and the laundry was still drying in the Cuban open-air.

Our everyday life was going to be "stopped" with some sort of dreadful stopwatch that would "freeze time" for many years to come.

Just before leaving, my mother looked up at her late father's pastel portrait, hanging up in the entrance hall of the house: "Can I take it?. .I can give it to some relative to keep for me?"- she asked them

"Yes you can, but you have to leave the frame behind"-they answered- “It’s probably valuable and it belongs to the Revolution from now on!”.

When we started taking off the frame, the very old pastel portrait ‘stuck’ to the glass. It had been framed 50 years before!. So, we pulled and pulled --and suddenly my grandfather's nose ‘stayed’ behind, clinging stubbornly to the glass!

"I guess you don't want it now"- said mockingly Cuca, the barber's wife, as my mother, sadly looked at the remains of the portrait . (I will never forget the woman hatred in her voice)

"Let's go"- added hastily my father, who had been called and had come to take us to my grandmother's house, where he had lived since their divorce in 1957- "Let's get out of here!"

I remember vividly when they put the official paper ‘seal’ on the door. A seal to protect our house. From what? And from whom?...(Two days after our departure the seal was broken- neighbors later wrote us- the big pieces of furniture and paintings removed by government officials; and later on the apartment was ransacked by anyone who wanted to go in and poke through our lives).

After the 'sealing of the house' we all went down to the main floor and since my father's car was not working -because there were no spare parts available to fix it, even for a respected revolutionary writer!- Marta and Jorge drove us in their car to my grandmother's house, where we would have to spend our last night in Havana .

That evening I went out with them. I did not want to stay at my grandmother's and spend hour after hour --like attending a wake-- counting the moments until the required 5am check-in at the airport. We ate at my favorite restaurant "El Carmelo", where instead of their usual delicious food all they had to offer was “Fried Eggs with Rice” ---and a funny tasting strawberry ice cream, made with a thick Bulgarian Fruit Jam, which created a weird ‘film’ that always ‘stuck’ to the roof of your mouth and we used to call “Numbing Ice Cream”!.. We said goodbye to some friends at the restaurant.. And we drove around an eerily dark Havana for hours.

I remember saying a silent farewell to streets and avenues and churches and stores and my school and the houses of friends. I remember riding along the Malecon as the waves hit the rocks and the air felt moist and sticky. I remember the silence in the car. The moment the neon signs were turned off and Havana turned dark and quiet.

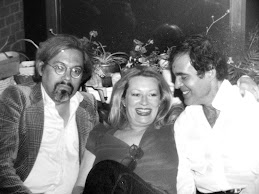

I arrived at my grandmother's very late, after saying farewell to my best friends. It was sad because Marta and Jorge were staying behind -and we had no idea if we were going to see each other ever again. Marta Larraz had become my close friend during the last 2 years; and from the moment I met her and her cousin Jorge Costosa, while we all took “English Conversation Classes” at a small school in Miramar ( which were supposed to "prepare" us for life in exile) we had become inseparable. Her family came from the city of Guantanamo, in Oriente province, where her mother and aunts -a admirable ‘clan’ of strong and hard working Cuban women- owned a small chocolate factory called La India. In Havana the great “entrepreneuses” sisters also owned a guesthouse for college students, where Jorge, Marta and Lolita, her mother, lived, surrounded by a dozen of handsome students from Guantánamo. Bright, daring and very ‘petite’, Marta -an only daughter adored by her mother- although was not a ‘wealthy’ girl in a snobish sense, got from Lolita whatever she fancied, and had received for a birthday gift a huge pale green Cadillac, which she drove with a self-assurance that never ceased to amaze me, (since I could not drive at all at the time--and did not learn until I was way into my 30’s! ) -and everytime we drove around Havana everyone stared at us. Two young girls in that huge car was quite a sight, specially in communist times, when everything in the country was upside down and anyone could ‘confiscate’ whatever they wanted "in the name of the Revolution".

That last night we drove and drove around aimlessly, going up and down Havana’s wide avenues, minute after minute, avoiding the moment of our farewells. When I finaly arrived at my grandmother’s house I never went to bed. And at 4:30am, still dark and cool outside, my Aunt Graciella drove us to "Jose Martí Airport". It was one of the saddest rides of my life.

After checking-in, the revision of the documents, the body search and the inventory of the "permitted items", began. It was humiliating to be bodily searched, but more humiliating was seeing my mother begging a soldier to let her keep the old silk scarf that had belonged to her mother. It was a memento of my late grandmother Mami had kept in a box since her death in 1958 --and even ‘smelled’ of her and her perfume.

"No, it's not permitted"- he screamed and 'confiscated' it in the name of the Revolution, amidst my mother's pleas

From my suitcase they took out two ‘prohibited items’ I had snuck in: an old pair of green cotton pants and a plaid wool pleated skirt "Pants and skirts are not in the list 'compañerita' (little comrade)…Don't you know how to read?".—the officer sneered

The cruelty of these "Cubans" at the airport and at the CDR's -was absolutely horrible and distinctive of the way many people behaved since the beginning of the Revolution .They all seemed so full of envy and resentment that, once again, they made me feel happy to be leaving behind such a crazy and ugly world. They happily took away my mother's silver bracelet (jewels were -of course- prohibited, unless you had a gold wedding band --and since Mami had divorced a few years before, "she did not qualify to take out of the country any kind of jewelry”). My brother had his comic books and sports magazines "confiscated". We weren't even allowed to take out of Cuba a single book to read on the plane!

These "regulations" had started almost 2 years before we left, and were absurd and unnecessarily cruel. The final humilliation, I guess. Or a way to test our patience and provoke an incident that would give them an excuse to cancel our departure. (Even “the though” of this possibility, still feels unbereably scary). So, once again, we shut up. Fearful to no end, even a slight gesture, or a sour expression, could be all the revolutionary officers needed to turn us back...Back to “where” though?... At this point we were non-entities, without a ration card ---and a house to return to!

Finally- at 10am- we were allowed to board the plane. Behind the glass walls of the 'pecera' (the fishbowl-like room where they held us for hours) I saw my friends Marta and Jorge. And my father crying like a baby next to them! According to him, we were not going to see him again. His love for the Revolution was such, that he had chosen to stay behind and not see his children ever again. It was all so sad, specially for my brother, who was so close to him. We all cried as we walked on the tarmac towards the plane.

But life is full of funny twists, and soon -as my mother softly cried, as the plane was taking us away from Cuba- I started to scream! Some very small worms were coming out of the wooden 'fashion beads' I had purchased at the Havana airport -- and they had started to crawl all over the front of my dress! This was especially offensive -and I took it as a horrible 'omen' for the future- since Castro called those who did not agree with the Revolution "worms" ---and because I had been so proud of the elegant dress I was wearing.

Trying to follow 'fashion' in the midst of a Communist Revolution had been almost impossible; and this dress was made from a design I had seen in the French magazine "L'Officiel" (found at the library of L'Alliance Française, where I studied French; and was a small oasis of western civilization in the middle of Socialist Havana) and later Lola - our marvelous Spanish dressmaker- made from a gray thick 'upholstery cloth' Mami had miraculously found in an old furniture store!

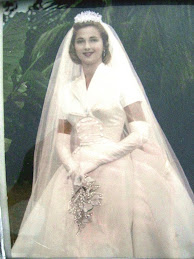

Changing gears into a more "frivolous" mode- I must tell you that in the midst of the worst scarcity, after 4 and a half years of Communism -and a very strict Ration Book imposed in 1962- women had to be 'inventive'; and not only I had this dress made, but the 2 others that composed my "permitted wardrobe", were made of thick silk shantung, which had been died black ---and it had come from the curtains of my Aunt Martha's home!...Just like Scarlet O'Hara had done, we imitated her sense of survival (for fashion's sake!) and dyed over 50 yards of white curtains (some in black and some dark blue) --and had dresses made for the entire family and even some friends. On the other hand , my gray "departure" dress -a YSL 'chemise' style and a jacket to match- was my pride and joy; and I had put it aside for 2 years, as we anxiously awaited the "Permission to Leave the Country". It was important for me to arrive in Mexico "in style", since relatives would be waiting for us at the airport -- specially my much admired and very stylish older cousin Purita, who had been one of Havana's best dressed young girls!

After killing the 'worms' -and taking off the rotten wooden beads- I composed myself and the flight to Mexico was fast and bumpy. My brother León was quietly sitting next to me and when he crossed his legs I noticed huge holes in the sole of his shoes. Poor León!. When two years before our departure we had requested permission to leave Cuba, Mami had put away a pair of shoes for each of us to wear on "the trip" --but since that time Leon's feet had grown, thus the much guarded shoes becoming useless --.and now he had to wear the only, and very worn out, pair that fit his ever-growing teenager's feet! . Mine were something else though! I was lucky my feet remained the same size 7 and I was wearing the square-toe Italian black pumps that I had put aside in1961. They were fashionable and exquisite and I did not mind the not very practical high heels.

Since I had been very young --after being a loyal admirer of the beautiful gowns worn by stars like Liz Taylor and Doris Day in American movies of the 50’s-- my love for fashion was immense, and leaving Cuba with only 3 dresses, a coat (most Cubans did not even owned 'coats' --and 'jackets' or '3/4 walking coats' did not 'fit the government’s requirements'!), 2 changes of underwear, 1 nightgown, 1 umbrella and 1 pair of shoes -as the Revolutionary Government ordered to all those leaving the country for good- was a terrible thing for fashion-conscious-me. Not only I was leaving behind my entire household, the few small jewels I owned and my bedroom filled with my books, my records and my memories ---but even clothes were 'forbidden' and restricted! So -when we were preparing to leave- my mother, always unselfish and wonderful to her children, allowed me to have 1 of her "3 allotted dresses", ending up with only 2 dresses for her ---and 4 for selfish me! (I ended up with actually 5, since the 'permitted' nightgown I took out of Cuba was a great violet chiffon spaghetti-straps dress, which -"sans" its zipper and closed with little satin bows- 'passed' as my sleeping gown, and later on became again a beautiful evening dress, which I wore for many more years) .

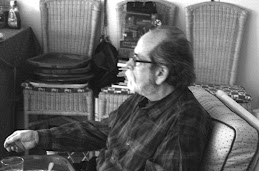

Two hours after we took off from Havana, the plane landed in Mexico City and a few minutes later -armed with his journalist credentials- François Baguer, an old Cuban friend of my mother's family, was inside Customs, helping us and practically screaming:

"Now you can speak out!...Speak out all you want my children!...Speak! ..Now you are Free!...Totally Free!"

I remember being struck by his exuberance and passion. It was so sweet of him to be there greeting us! My mother immediately started crying. He held her tightly, as tears rolled down his old and wrinkled cheeks. François had been one of the best friends of my mother's older and very beloved brother Paco Ichaso, who had died unexpectedly in Mexico City, during the October 1962 Missile Crisis, just 5 months before our arrival.

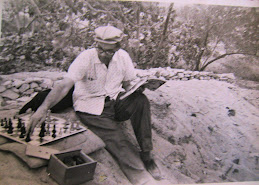

"Tito Paco" had been one of Cuba’s young patriots in 1933, when he fought President Gerardo Machado --an elected President, who became ‘persona non grata’ when he ‘dared’ to re-elect himself into a second term, which gave way for a strong opposition. He also had been one of the authors and signatories of the advanced Cuban Constitution written in 1940. A lawyer at age 19, a fair man, with tremendous serenity and always in a good mood --and one of the most brilliant and highly respected Cuban writers of this century-- he had been my favorite uncle and a ‘father’ figure throughout my life. One of my ‘educators’ since I was a small child, frequently taking me to the theatre, ballets or operas and letting me borrow ‘key’ books from his wonderful library, which he always kept so chilly I had to wear a sweater to enter it! .

When Renata Tebaldi sang in Havana in 1958 I saw my first and unforgettable “Aida” with Tito Paco and his wife 'Tita' Mary at the Havana Auditorium; and it was right there that I started loving the ‘magic moment of anticipation’ that takes place just before the curtains part at the beginnning of a ballet -or a concert- in a huge and brilliantly lit theatre. When I was about to turn 15 he had promised that my “15 Birthday Gift” would be a trip to Europe with him and my aunt the following summer -- and planning it became my obsession for many months, researching maps and books about European cities and museums all over the continent. This pleasurable planning became my hobby for months, to the extend that I practically memorized the maps of every city. That trip never took place because of the arrival of the Revolution, and the day when I finally visited Paris -many years later, already in exile, I walked around the boulevards like I had lived there all my life.

When our family unit desintegrated, and one by one all the members of the extended family began to leave the island, fleeing into exile in the early 60’s, my dear Tito Paco ended up in Mexico City, from where he had become the 'force' behind our efforts to leave Cuba, constantly calling us, sending us visas and all kinds of help. He wanted us in Mexico as soon as possible and did all he could to help get us out of Cuba before my brother turned 15, thus becoming eligible for Cuba's ominous Military Service, and forbidden to travel abroad. (We were terrified he could be sent to fight for Communism in some foreign land, like it later happened to many young Cuban men sent to Angola, Somalia, etc.). If we had not been granted our permit to leave in March, and Leon had been in Cuba just a few months later -by August - all of us would have stayed in Cuba forever, and these memories would be 100% different. Four months -just 120 days- changed our destinies.

All those memories rushed to me that cool March morning at Mexico’s airport as François urged us talk freely and ‘be happy’.. Ironically, instead of Tito Paco welcoming us, it was his best friend who took his place! Still, we were afraid 'to speak out', even after François's urgings- as we came out of Customs and faced The Family

After hugs and kisses and lots of tears, my cousin Purita looked down at my divine Italian shoes and exclaimed: "Oh my God...Where did you get those old horrible things!...Those 'catanas viejas'?"

Can you imagine a blunter and deeper fashion ‘blow’?

I could not believe it! …In front of her husband my cousin Julio, my cousin Marilyn and her husband my cousin Alberto, those first words sent me into a frivolous tailspin of 'wounded fashion pride'. How in the world could she call my beautiful and much guarded shoes 'old' and 'horrible'? I think my mother noticed my hurt expression, because she immediately changed the conversation calling everyone's attention to Leon's own hole-filled moccasins, which seemed about to disintegrate.

"Can we try to get him some shoes?" -she begged- "He cannot walk around with these anymore". Her words were a ‘command’ to her nieces and nephews, who were really eager to be kind and help us as much as possible --and very soon we all climbed in a beat up station wagon and drove through the ugly streets that surround Mexico City's airport, towards a huge store called "Gigante".

True to its name, it was a giant Wall-Mart style cheap store, and when we entered it ---it was like finding a "mirage"! After years of scarcities and the meager things we got to eat through the Ration Book, a common pastime in Cuba had been to talk (and dream about) many things that had disappeared from our lives. Specially food. I remember imagining giant Banana Splits, talking incessantly about delicious ham and cheese sandwiches, thick steaks, canned Libby's peaches and fresh red shiny apples. And in "Gigante" we found all this and more!..It was just too much all of a sudden; and it made me and my mother very dizzy and extremely confused.

"Look Leon...ham!"..."Oh, my God, look at all these cheeses"... "Watch mommy, all these shoes!"

Finally a pair was found for Leon. I remember them horrible; made of a carton-like plastic to resemble leather, with a side strap and a metal buckle.. They seemed huge, but they fit his teenager feet and a little more! Since we were not going to be able to afford to buy him shoes every 3 months, the 'consensus' was to buy them 'much bigger than his true size'.

.

After the Gigante experience we were really overwhelmed. Dizzy, car-sick and very hungry --- suddenly all I wanted was to get on the next plane and return to Cuba and my little bedroom. Fast! Fast! "Oh please God, get me out of here, oh please!"- I prayed in vane. You see, I was not ready for all this sudden 'fuzz' about us. We were again in a 'normal society' - and after 4 years of communism- we were somehow 'conditioned' to live with less freedom, less consumerism and less independence to make choices. It was a tough new beginning for sure!

.jpg)

.jpg)

+azul.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)